TOMMI PARZINGER

Tommi Parzinger (1903-1981) may not be a household name, but his unique contribution to 20th Century design certainly deserves a mention. He was raised in Germany but made his mark in the United States, where his consummate craftsmanship was cherished by his well-heeled clientele, making him a stylish fixture on the post-war Manhattan scene. He designed everything from silverware to fabric, furniture to perfume bottles, all to the highest standard. As interior designer Nancy Chase stated, “he was a Renaissance man in the sense that there was nothing he couldn't design”.

Tommi Parzinger at work, date unknown.

Born in Munich to creative parents, Anton Parzinger (later Tommi) enrolled at the local Kunstgewerbeschule where he trained in applied arts including glass, ceramics and metalwork. Clearly his vocation did not elude him; he was a natural craftsman. Upon graduating, he worked as a freelance furniture designer across Germany and Austria, acquainting himself with avant-garde Modern movements such as the Bauhaus, Jugendstil and Wiener Werkstätte.

In 1932, he won a poster design competition. The prize? A trip to the United States on the S.S Bremen; an experience that would introduce Parzinger to the dazzling country that would become his home for the next five decades. During the 1930s, Britain and the U.S. benefitted greatly from an influx of talented emigré designers fleeing the turbulent rise of Nazism in Europe (Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer and Anni Albers to name a few). He settled in New York City in 1935 and never looked back. I’m not sure whether this was the point that Anton became Tommi, but it does have a New York ring to it.

Design for three-piece smoking set in silver, c.1950-70.

Designs for salt shakers, c.1950-70. Images courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum.

He began designing refined tableware and furniture for Rena Rosenthal, who ran a ritzy interiors shop on Madison Avenue. It's here he would have learned to cater to American tastes for elegant conservatism, whilst still pursuing Modernism in form. In 1938 he started designing for Charak of Boston and a year later, founded his own furniture firm Parzinger Inc complete with a swanky showroom on East 57th Street.

Stylistically, his pieces are perfectly proportioned and delicately decorated. Unlike some of his Modernist contemporaries, Tommi didn’t shy away from ornamentation. Every detail was considered - the hand-polished lacquer on a four poster bed, the etched brass hardware on a cocktail cabinet, the mahogany burl veneer on a coffee table with delicate brass feet. In this way, his designs have more in common with French Art Deco designers of the 1920s, such as Louis Süe and André Mare, whose pieces were sumptuously adorned with rare woods, silk fabrics and inlaid ivory.

In 1946, he asked friend Donald Cameron to become his business partner and for the next 20 years, they catered to a coterie of elite decorators and their clients. The Fords, Rockefellers and Marilyn Monroe were among the American cultural heavyweights who commissioned Parzinger furnishings for their homes. Two more showrooms were opened, displaying everything from credenzas to candlesticks, cabinets to cigarette holders. He was also a master draughtsman, producing flawless technical drawings of his ideas. “He could do anything; it was frustrating and inspiring” recalls Cameron.

Mahogany and brass coffee or cocktail table, designed for Charak, 1950s

Design for silver candelabra, date unknown. Image courtesy Cooper Hewitt Museum.

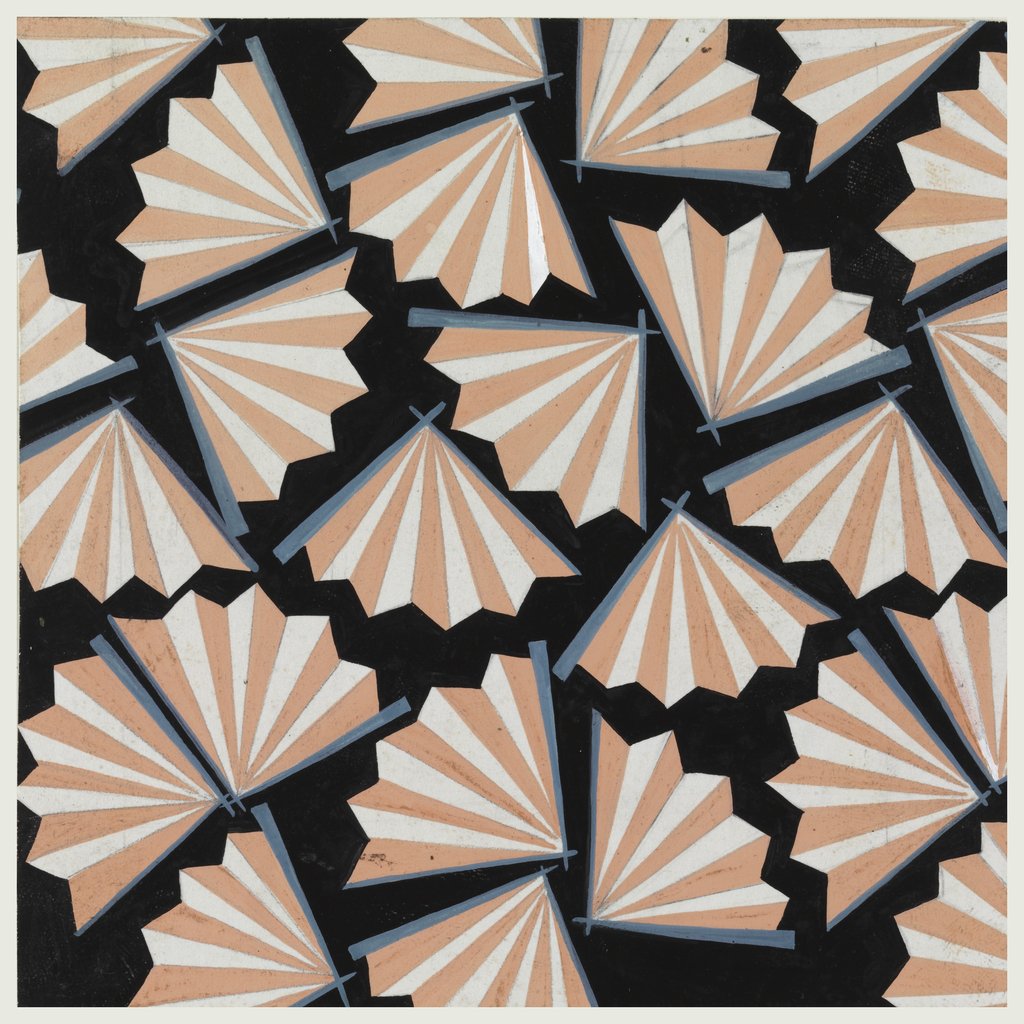

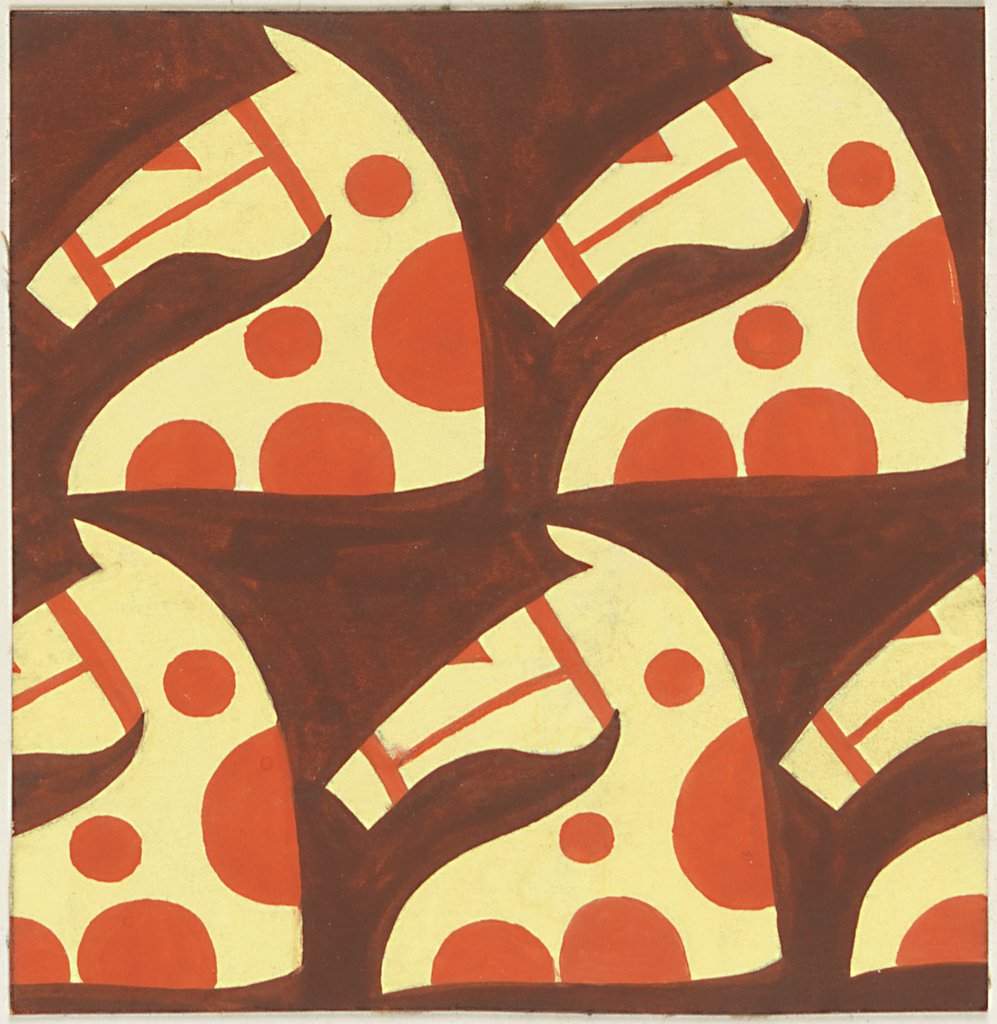

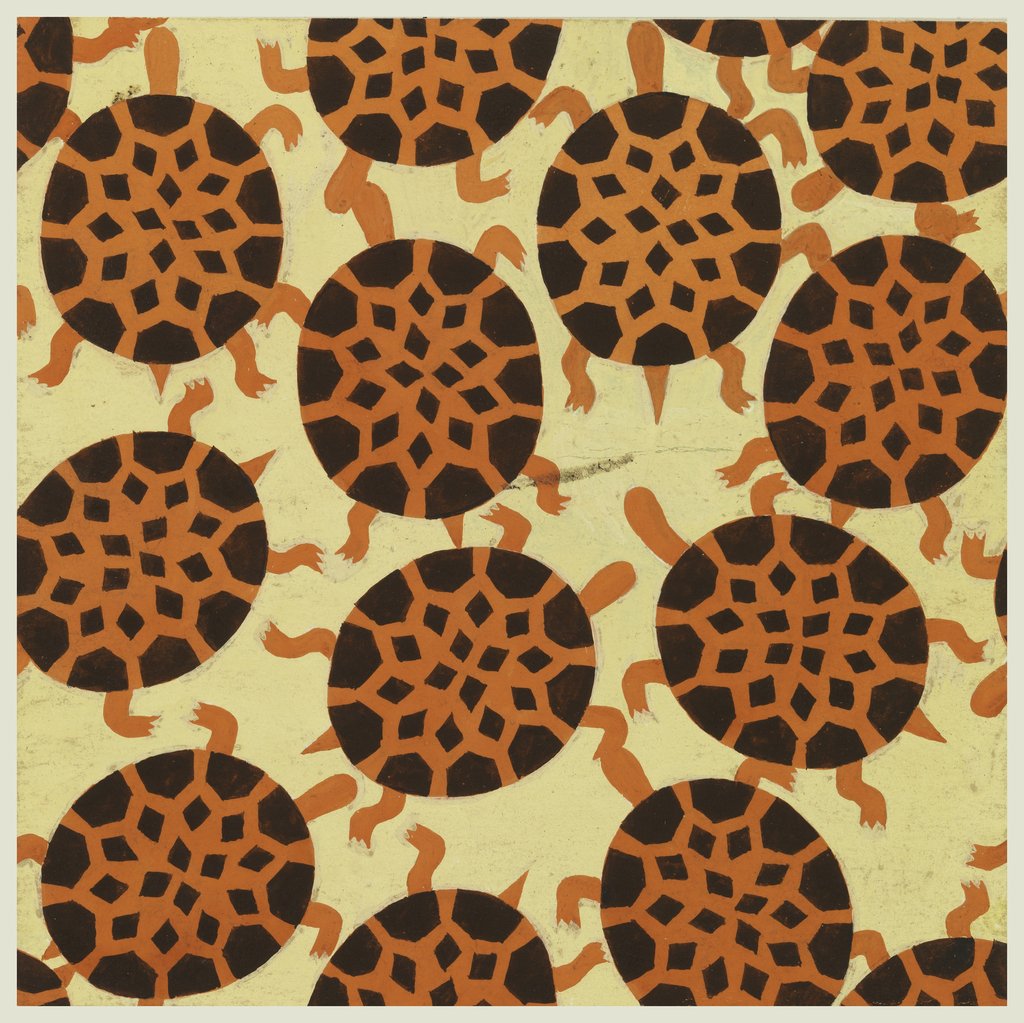

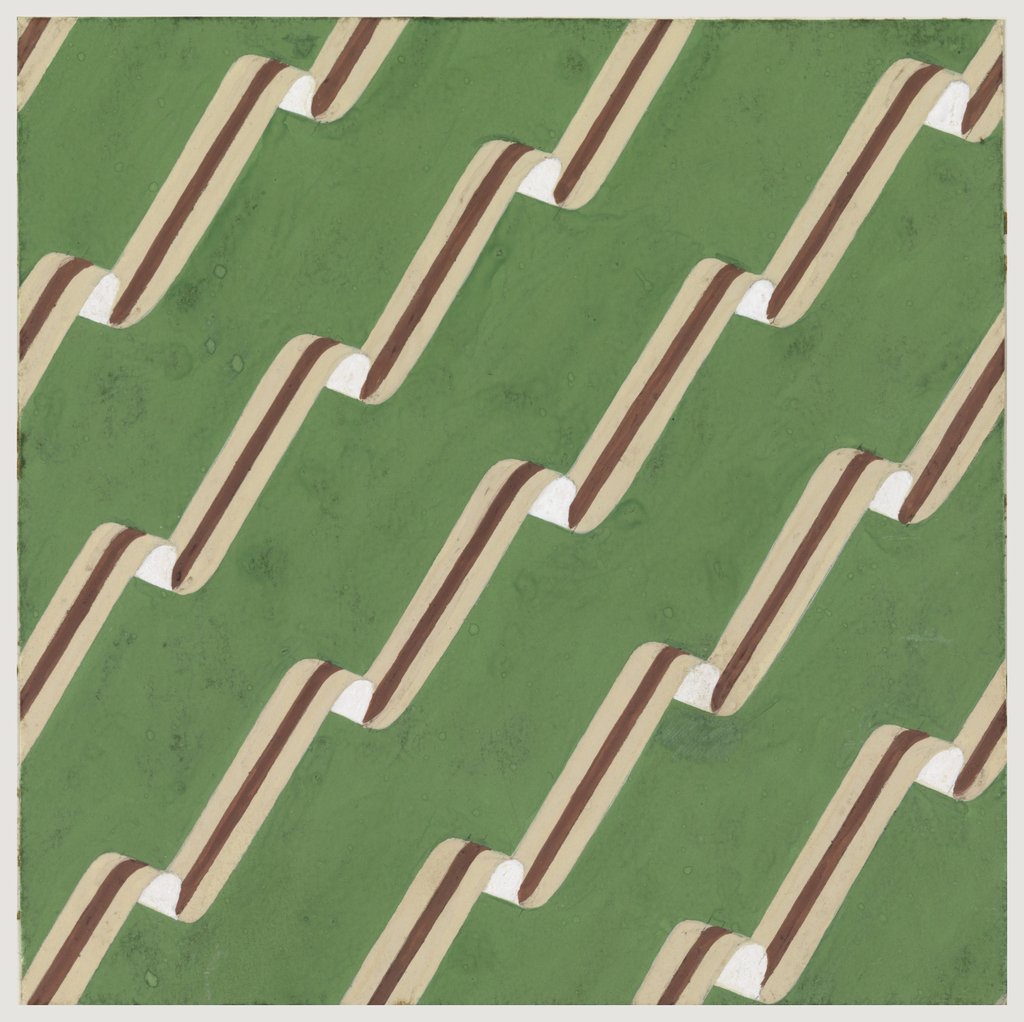

Naturally, I’m drawn to his pattern designs for fabric and wallpaper, many of which are held in the Cooper Hewitt Museum archives. The conversational prints reveal a more playful side to Tommi’s work; motifs like turtles, beach balls and parachutes all dance across the paper in powdery gouache. Still elegant, but whimsically so. I can see the influence of the Wiener Werkstätte here - for them no motif (however surreal) was off limits, as long as it was executed in a contemporary way. Most of these prints were designed for other firms, but he sometimes incorporated unique fabrics into his in-house pieces.

Parzinger held high-minded views on design reform. In a 1943 article in Craft Horizons, he castigates the current state of design and laments the age-old problem that mass-production creates for the craftsperson: “if one looks at objects produced for use in our homes … they give quite a depressing picture of disintegrated taste, inexpressiveness, inner emptiness, lack of fantasy and trite sentimentality.” He described the need to embrace design ideals as a “spiritual decision”, not merely one of taste.

Above: five designs for textiles, gouache on paper, c.1930-1950. Images courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum.

It’s said that from 6am to midday, Tommi would paint from his home studio before starting design work. In the last 15 years of his life he focused only on Expressionist painting; perhaps after decades of exacting discipline at the drawing board, he was ready for a more relaxing pastime. Following his death in 1981, Donald Cameron kept the legacy alive by reissuing certain designs in partnership with New York antiques dealer Patricia Palumbo (as Tommi would have insisted, only the finest craftspeople were enlisted for the task).

Tommi Parzinger represents a certain ‘high-style modernism’ that entices collectors but seems to garner less acclaim than his more radical peers. Although his style is distinctly American, his grounding in European craft lends it a traditional feel - ‘Munich meets Manhattan’ if you will. His designs were elegant but never staid, charming but never twee, and they conjure up an image of mid-century New York City that makes me want to step back in time. I’ll just have to watch Mad Men (again) instead.