RUTH REEVES

Screen printed silk scarf, 1930. Image courtesy of ruthreeves.com.

Ruth Reeves (1892-1966) was an artist and textile designer known for her witty, dynamic and distinctly American fabrics. Born in Southern California, Reeves spent the 1910s studying at various US art schools, including the Pratt Institute in New York City. Although post-studies she landed a job as an illustrator for Women’s Wear magazine, Reeves’ creative curiosity and ambition took her to Paris in 1921 to study painting under the avant-garde artist Fernand Léger.

Figures with Still Life, wall hanging for W & J Sloane c.1930. Image courtesy of ruthreeves.com.

Dress made from Play Boy fabric, screen printed linen for W & J Sloane c.1930. Image courtesy of Met Museum.

The seven years spent in Paris were extremely formative for Reeves. Not only was she introduced to Cubism and Modernism through Léger, but to artists like Raoul Dufy who were pioneering the artists’ textiles movement (she may well have got to know Sonia Delaunay too, as she was a frequent visitor to Léger’s studio). Dufy’s influence on Reeves’ early fabrics is clear - they both created narrative prints depicting tableaus of ordinary life, as seen in American Scene and Kitchen. Galvanised by her Parisian stint, Reeves returned to the States in 1928 and began independently screen printing her own fabrics, using motifs drawn from her own domestic life as a mother raising three daughters. At the time, incorporating such prosaic motifs into textiles was a novel concept; the press dubbed Reeves’ designs ‘personal prints’ (in this way, they remind me of those by Footprints Studio, who I wrote about in an earlier blog post).

Kitchen, screen printed cotton for W & J Sloane c.1930. Image courtesy of ruthreeves.com

Until this point, Modernist design was seen as a European aesthetic yet to be assimilated in the US, but Ruth Reeves was one of a handful of designers keen to create a more cohesive ‘American Moderne’. A quintessential manifestation of this was the undeniably jazzy interior of New York’s Radio City Music Hall built in 1932, for which she was commissioned by Donald Deskey to design a large foyer carpet and wall covering.

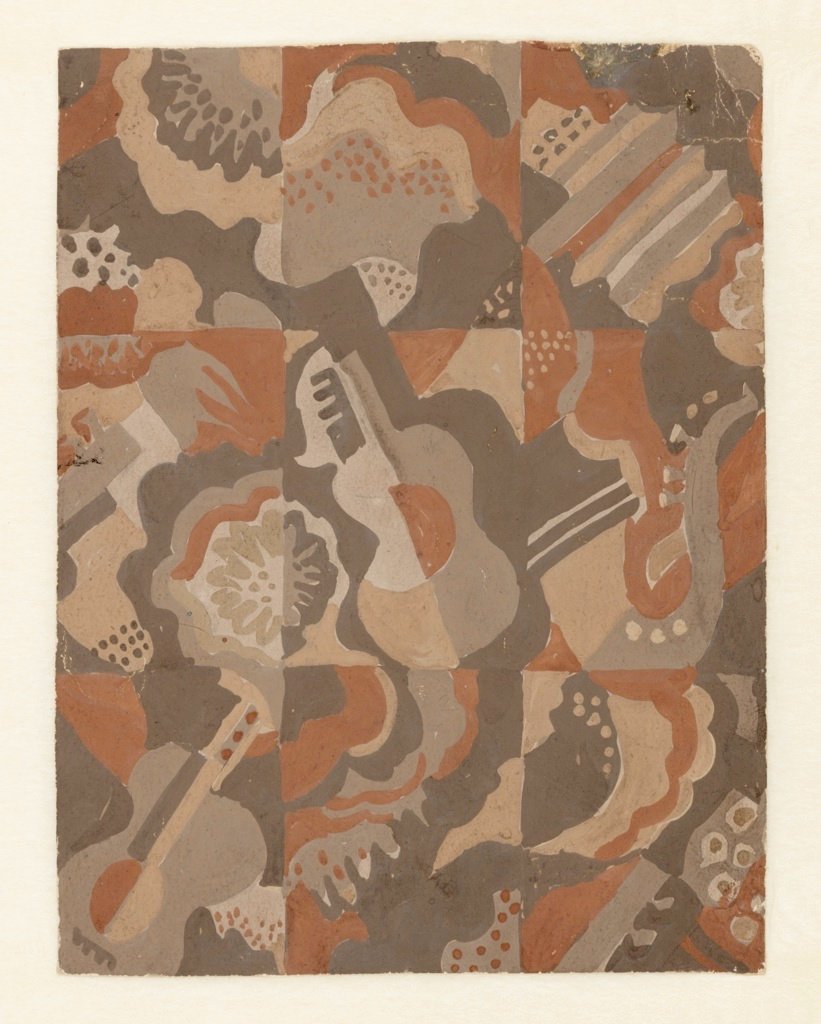

The music hall was a spectacular statement of Art Deco and Reeves’ carpet design - a lively Cubist-inspired pattern of musical and abstract motifs all jostling for space - simply screams ‘jazz age’. I particularly love the wall covering she designed titled The History of Theatre, a joyful melee of dancers, theatre-goers and circus performers screen printed onto fabric in two colours. She utilised the screen printing method (in which ink is pulled through a stencil) expertly, allowing negative space to act as a third colour in the design.

The History of Theatre, screen printed wall hanging designed for Radio City Music Hall, NYC, 1932. Image courtesy of 1dibs.com

Radio City Music Hall foyer, feat. Reeves carpet design Still Life with Musical Instruments, designed 1932.

Gouache carpet design for Still Life with Musical Instruments, 1932. Image courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum.

Her aptitude for screen printing is particularly impressive seeing as the technique was not widely used in Europe or America until at least the mid-1930s. Whitney Blausen suggests she may even have been the first American to experiment with screen printing, and certainly the first to employ it so ingeniously. Although she mastered the modern, Reeves had a lifelong fascination with traditional craft, particularly from South America and India. In 1956, aged 64, she was awarded a Fulbright grant to travel to New Delhi, where she lived and worked, studying Indian textile techniques, until her death eight years later.

What fascinates me about Reeves was her ability to marry art, design and craft. Her fabrics were more often exhibited in galleries than mass-produced for commercial use; consequently she never got rich from her work, but she was able to maintain total creative control. Throughout her life she held firm in the belief that “fabric design rightfully belongs in the category of the Fine Arts … it is just as important as good architecture, and certainly is more closely associated with our everyday living than are paintings.”

Reeves (right) and a female assistant working on a mosaic mural. Photographed for the Works Progress Administration, NYC 1940. Smithsonian archives of American art.