ILONKA KARASZ

Ilonka Karasz (1896 - 1981) was a Hungarian-American designer and illustrator. During her six decade career she worked across an astonishing array of media, including wallpaper, textiles, ceramics, furniture and silverware, blending folk art with Modernism. Best known for her illustrated covers for The New Yorker magazine, she is a significant yet surprisingly overlooked figure in 20th Century design history.

Born in Budapest, Karasz studied at the city’s Royal School of Arts and Crafts, before emigrating to New York in 1913. Amidst Europe’s ominous political landscape, it was not unusual for designers to seek opportunities across the Atlantic. Her European arts education, which was guided by the modern principles and aesthetic of the Wiener Werkstätte, clearly stood her in good stead. Upon arriving in Greenwich Village she quickly found work as an illustrator for several avant-garde magazines, aged just 17. Despite being described by one peer as “the hermit painter”, she quickly established herself as a respected, if enigmatic, artist on the bohemian Village scene.

Envelope for Paul Frankl Galleries, New York City, woodcut on paper, c.1925. Image courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum

Cover for The New Yorker Magazine, May 1925

Karasz’s work turned heads. She won a textile design competition sponsored by Women’s Wear magazine and secured a job designing advertising imagery for ritzy department store Bonwit Teller - an impressive assignment for a 19 year old. After this flurry of fledgling success, Karasz moved to the more suburban environs of Brewster, where she and her husband Wilhem built the home in which she would live for most of her life. The eclectic interiors were featured in House Beautiful magazine in 1928. Around this time she turned her hand to industrial design, producing silverware, ceramics and furniture in an angular and ornament-free style inspired by the De Stijl movement. Karasz contributed to several important design exhibitions in the late 1920s, including one held by the American Designer’s Gallery, where she was the only woman asked to curate entire rooms. She designed a studio and a brightly coloured nursery, described by Arts and Decoration magazine as the first nursery “ever designed for the very modern American child.”

By 1935 she had also established herself as a prominent textile designer, working for leading fabric houses like Schumacher, Cheney and DuPont-Rayon. Oak Leaves, a striking and distinctly Art Deco pattern was screen printed onto mohair and received praise across the industry. Not only was she was interested in the decorative design of textiles, but in the structural qualities of fabric as a utilitarian material. DuPont Rayon employed her to help them improve the quality and texture of their rayon and she became one of few women to design fabrics for cars and aeroplanes. Her 1930s work reflects the increasing popularity of Art Deco, as seen on a range of ceramic plates manufactured by Buffalo Pottery, which depict pretty vignettes of animals, trees and florals in a Deco style.

Rougeware and lamelleware plates, manufactured by Buffalo Pottery, 1935. Images courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum

Oak Leaves, screen printed mohair, manufactured by Lesher-Whitman, c.1928. Image courtesy of RISD Museum

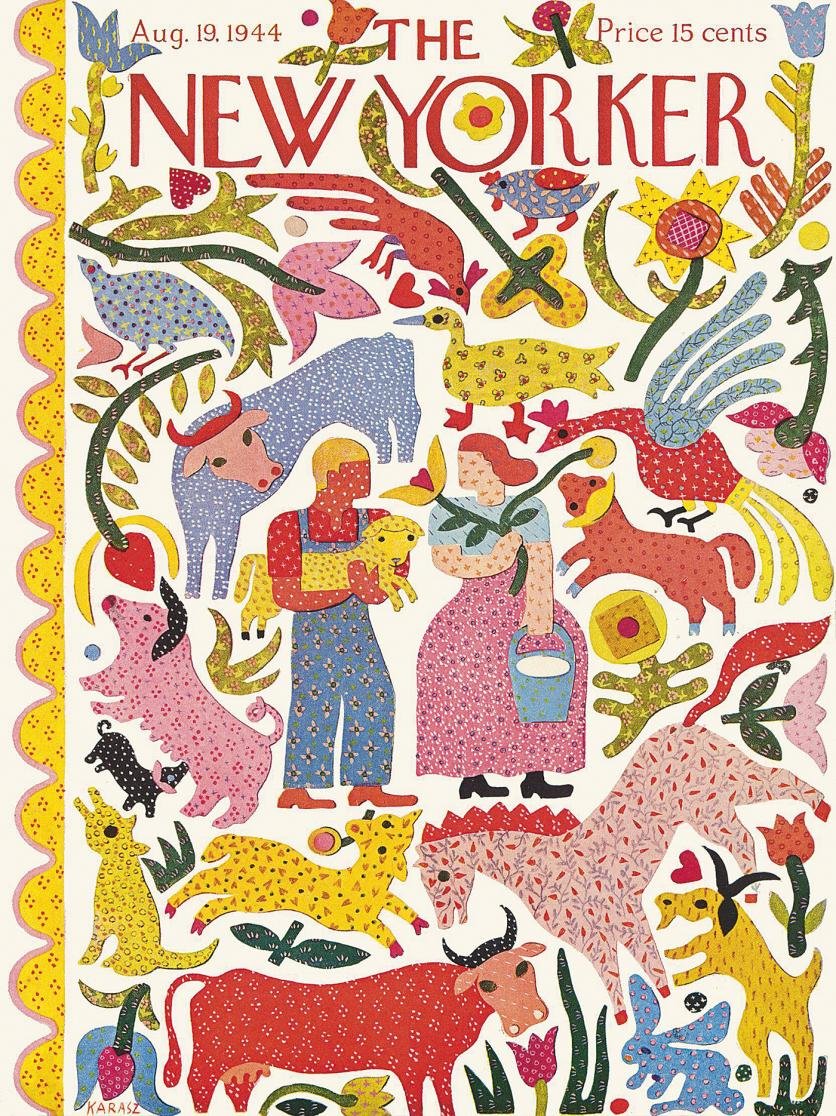

Karasz’s illustrative work found its home on the covers of The New Yorker magazine. Between 1925 and 1973 she created 186 covers for the iconic publication, meaning millions of Americans would have enjoyed her art on their coffee tables. The covers often portray city scenes brimming with raucous life, inviting the eye to traverse the page (it brings back memories of scouring Where’s Wally books as a child). Her illustrative style is detailed, playful and almost childlike in composition (and I mean this as a compliment; it’s a quality artists like Picasso and Matisse spent decades trying to capture). Much of it feels reminiscent of contemporary illustration.

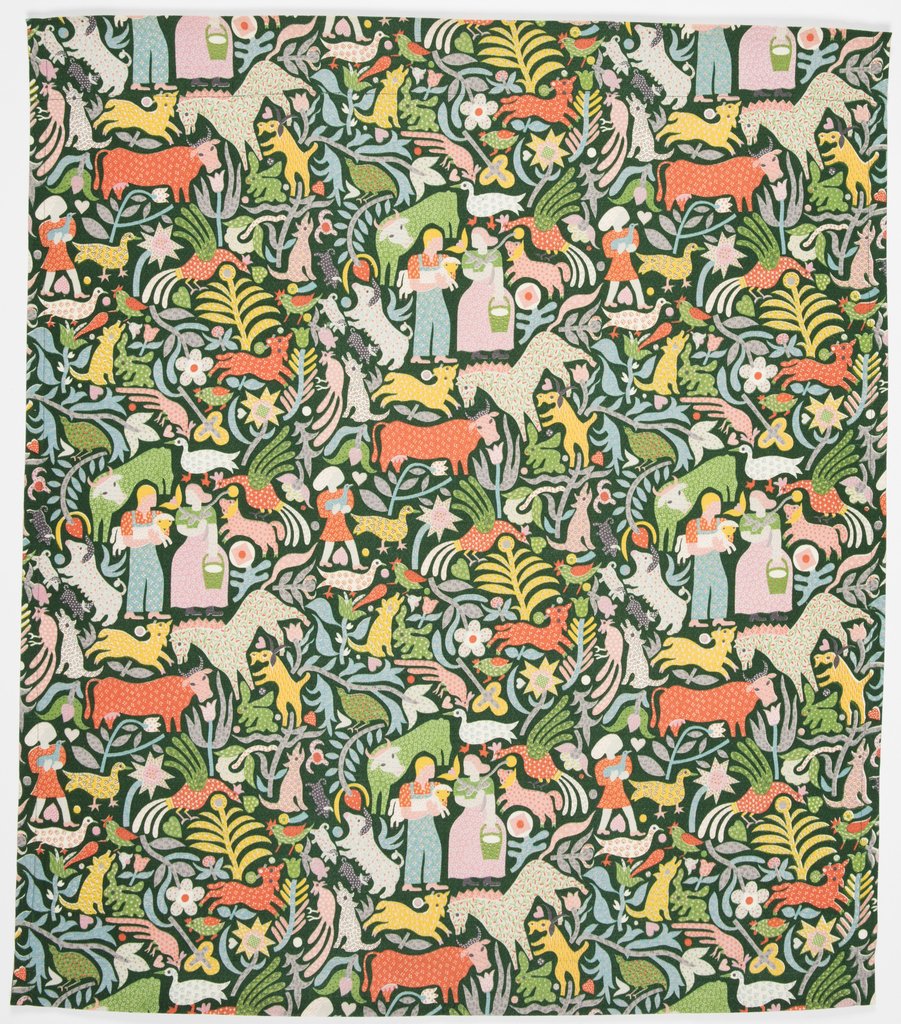

Throughout her life, Karasz was inspired by folk arts of her native Hungary as well as South America. The nod to folk art is particularly prominent in a The New Yorker cover from 1944 - a planar scene of two farmers surrounded by colourful flora and fauna, which look as though they have been collaged from pattern papers. The result is charming and unpretentious. She later adapted the illustration to create a furnishing fabric named Calico Cow - this time on a dark green ground - sold by Youngstown Kitchens.

millions of Americans would have enjoyed her art on their coffee tables

Cover for The New Yorker Magazine, August 1944

Calico Cow, printed cotton, manufactured for Youngstown Kitchens, 1955. Image courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum

The 1940s and 50s saw Karasz focus on wallpaper, producing many designs for New York firm Katzenbach and Warren, where she often depicted natural forms in her signature flattened perspective. Recognised for her material innovation, she was commissioned by ALCOA (Aluminium Company of America) to explore aluminium as a wallcovering material in 1957.

Sadly by the time she died in 1981, aged 84, Karasz’s status had significantly dwindled. American design history tended to focus on prominent male figures who contributed singular ‘classics’ to the canon (excuse me while I roll my eyes). Her extraordinary versatility may have diluted her legacy, but this very trait is what makes her a true 20th century pioneer. So much more than a successful illustrator, Ilonka Karasz was a highly skilled designer with a working knowledge of many materials. Through her skill and industriousness she undoubtedly helped Modernism to flourish in America.

Machine printed wallpaper sample, produced by Katzenbach and Warren inc., 1948. Image courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum

Ducks and Grasses, screen printed wallpaper sample, produced by Katzenbach and Warren inc., 1948. Image courtesy of Cooper Hewitt Museum