ÉMILE-JACQUES RUHLMANN

This month (April 2025) marked 100 years since the birth of Art Deco, or more precisely, the start of the Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes, which opened its (beautifully crafted) doors to the public in Paris on 28th April 1925. I’m continuing my celebration of this spectacular event by focusing on one of its key figures - Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann.

Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, c.1928

Ruhlmann (1879 - 1933) was a Parisian furniture and interior designer whose style epitomised the more luxurious end of the Art Deco movement. The pinnacle of his career was arguably the pavilion he furnished and decorated for the Paris Exposition in 1925. Known for employing lavish materials and exquisite craftsmanship, Ruhlmann was dubbed "the Riesener of the 20th century” (Riesener being the royal cabinetmaker to Louis XVI). His furniture pieces are still highly sought after by collectors today, fetching eye-watering prices at auction.

Born in Paris in 1879, Ruhlmann (known to close friends as Milo) was introduced to the world of interiors at an early age as his father ran a decorating and construction business named Société Ruhlmann. After his father’s death in 1907, he readily took on the family business, marrying his wife, Marguerite Seabrook, the same year. In 1910 he tasked himself with designing all the furniture for their new apartment, going on to exhibit them at the Parisian Salon d’Automne and Salon des Artistes Décorateurs. In 1919, he established a new business with friend Pierre Laurent named Ruhlmann & Laurent, which specialised in fine furniture, lighting and textiles for a well-heeled clientele.

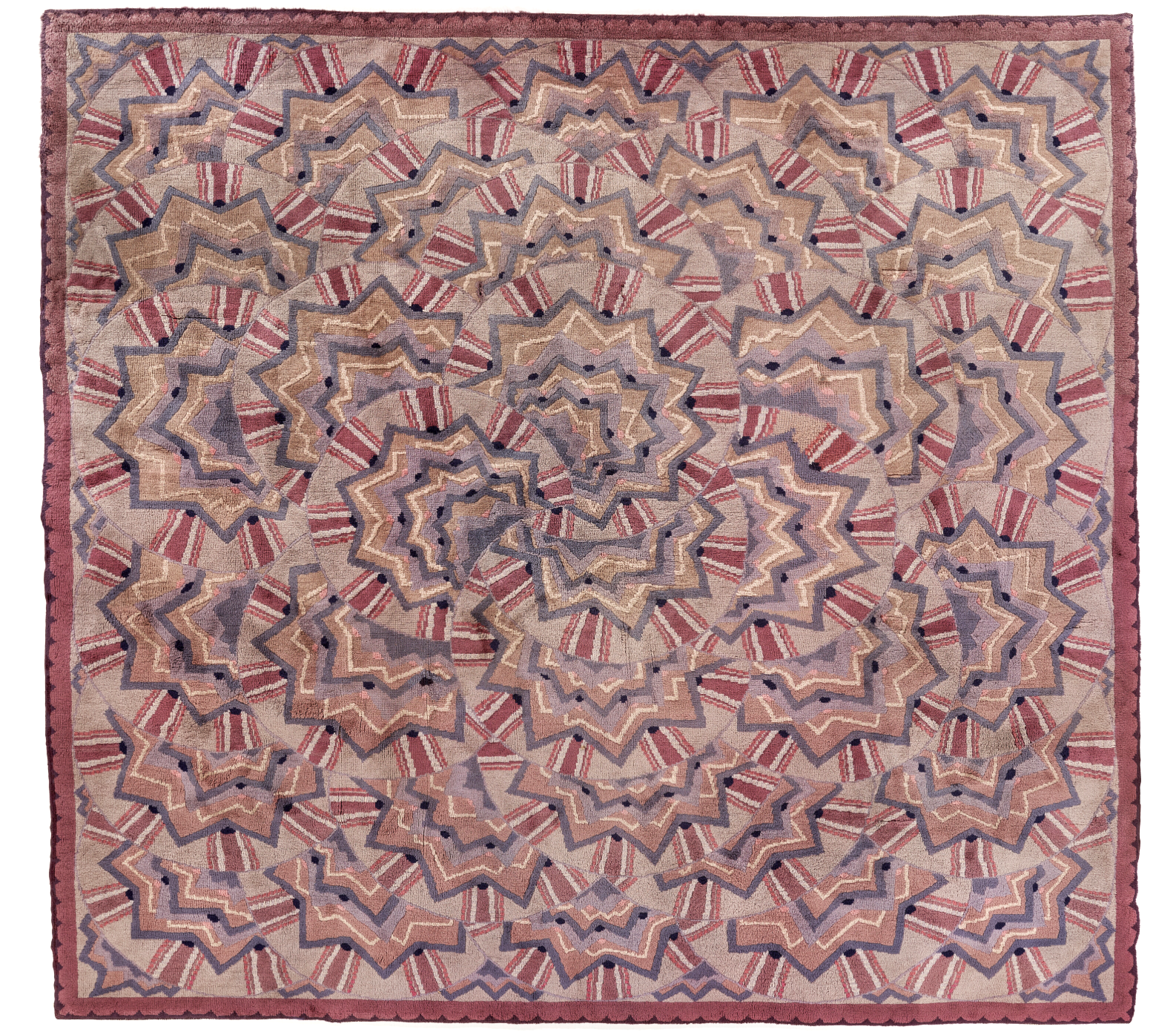

Hand-knotted wool rug, c.1925. Image courtesy Christies.

État cabinet, c.1923. Image courtesy Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

A typical Ruhlmann piece would be crafted from rare imported woods such as Amboyna burl or Macassar ebony and impeccably inlaid with ivory, ebony or sharkskin detailing. Delicate tapered legs were a hallmark feature, lending the pieces grace and poise. One well-known piece is the État cabinet, commissioned for the Met Museum in 1925. The cabinet flaunts a floral bouquet crafted from ivory and ebony marquetry, Amaranth veneer, red satinwood interior and a subtle peppering of ivory detail. The designer admitted that each piece was a labour of love, which, despite the exorbitant price tag, lost him money. It’s said that one piece of furniture could take eight months to complete and set you back the cost of a large house.

Ruhlmann was an elitist, but unabashedly so. While many design pioneers of the early 20th century were concerned with democratising design as a force for social good, he confronted the fact that new design styles were invariably propagated by the wealthy because they could afford the time and craftsmanship involved. During a magazine interview in 1920 he stated: “Only the very rich can pay for what is new and they alone can make it fashionable. Fashions don’t start among the common people.”

Ruhlmann (centre) with his design team at 27 Rue de Lisbonne, Paris, c. 1931

Writing desk made from Amaranth, inlaid with ivory with carved ivory handles, c.1925

Aesthetically his influences were a blend of Neoclassicism, Art Nouveau and Arts & Crafts, although he didn’t wish to associate himself with any one school. His primary aims were timelessness, elegance and extremely high quality. Despite an affinity with his materials, Ruhlmann was not a trained craftsman nor cabinetmaker. He was said to carry a notebook at all times, sketching new ideas whenever they struck, which would then be refined to a full-scale working drawing before being brought to life by trusted craftspeople. In 1923 he established his own furniture workshop on Rue Ouessant, allowing him to oversee the full process. Within four years this workshop had grown to employ 27 master cabinetmakers, 25 draftsmen and 12 upholsterers as well as experts in gilding, lacquering and marquetry.

It’s no surprise, then, that the pavilion Ruhlmann designed for the 1925 Exposition Internationale in Paris, was titled the Expo’s “most spectacular event”. The Hôtel du Collectionneur pavilion was the imagined palatial home of a wealthy art collector, filled with Ruhlmann’s furniture pieces nestled amongst modern paintings, ceramics and metalwork by his French peers. The rooms were admired by hundreds of thousands of visitors and brought his work to the international stage. He subsequently acquired new and notable clients, including fashion designer Jeanne Paquin, the Rothschild banking family and Eugène Schueller, founder of L’Oreal. His pavilion was criticised, however, by Modernist designers like Le Corbusier, who favoured pared back functionality over excessive luxury.

Top: Ruhlmann’s pavilion at the Paris Expo, 1925. Architect Pierre Patout. Bottom: Main salon inside the pavilion, 1925.

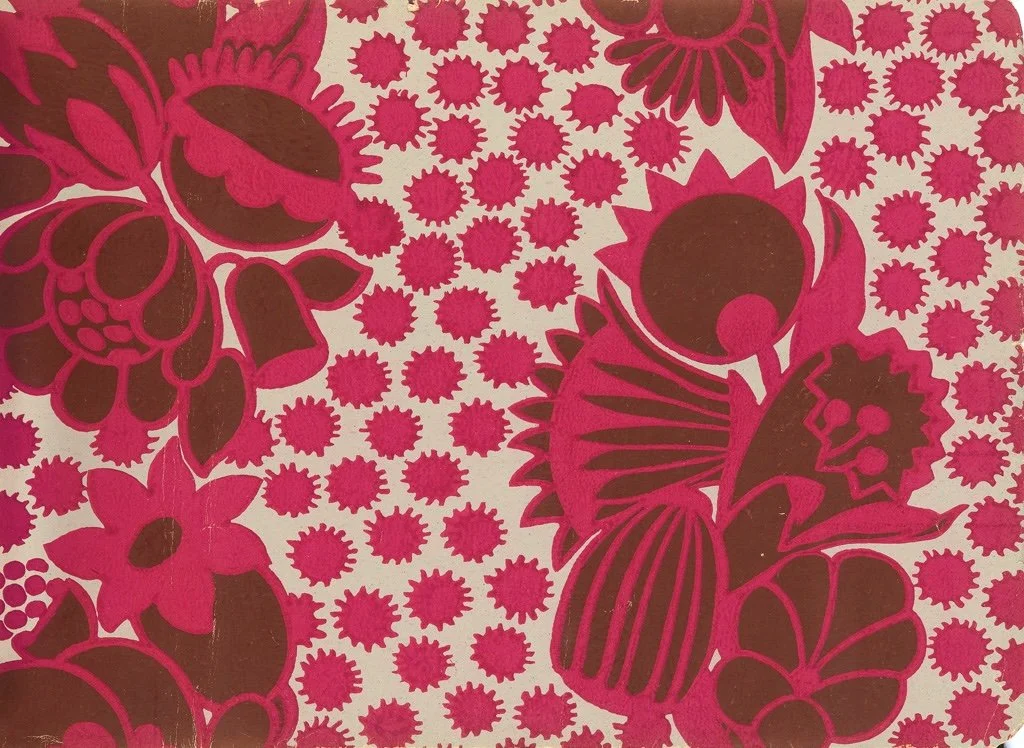

Ruhlmann also designed textiles and wallpaper, although few examples remain. These designs are surprisingly colourful, made up of playful semi-abstracted florals block-printed in vibrant colours. I see similarities with E.A. Séguy and Edouard Benedictus. The use of thick dark outlines, a motif seen in Art Nouveau, is reminiscent of stained glass. When looking at black and white photographs, it’s easy to forget that Art Deco interiors were rich in colour, as seen in Ruhlmann’s interior schemes rendered in gouache. Rugs, drapes and murals bring the rooms to life with deep plum, acidic citrine and olive green tones. Indeed, he was invested in every aspect of the interior, from lighting to doorknobs to architectural elements.

Ruhlmann’s life and career was curtailed by a sudden illness that led to his death in 1933. It’s hard to say how his business would have survived the Second World War, given his refusal to spare any expense on craftsmanship; both demand and availability of materials would have surely diminished. Upon learning of his terminal illness, he instructed that his business be dissolved after all remaining orders were completed. This savvy decision to secure his legacy crystallised his unique contribution to design in a particular moment of time. As a result, his name will be forever synonymous with Art Deco.

Two block-printed wallpaper samples, c.1919

Interior scheme in gouache, from portfolio Harmonies: Intérieurs de Ruhlmann, 1924. Image courtesy of Ruhlmann.info